Driving down the road this week in Conakry, the capital city of Guinea, I saw large banners highlighting World Malaria Day on April 25. Guinea, sandwiched between Mali, Senegal, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea Bissau in West Africa, is one of the poorest countries in the world and is also hyper-endemic for malaria. It experienced an estimated 4.79 million cases in 2016, out of a total population of just over 12 million people, with children under five years old suffering the worst of the burden. However, there were only an estimated 9000 deaths, representing a huge improvement even in the last few years, due in large part to the support from external programs such as the United State President’s Malaria Initiative, which has recently concluded a massive multi-year, country-wide malaria control effort. In countries like Guinea, World Malaria Day is an opportunity to re-energize advocacy and control efforts each year, and refocus for the continued fight against malaria.

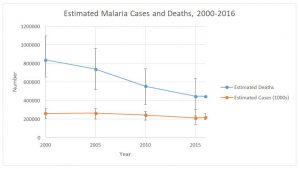

Graph of estimated malaria cases and deaths between 2000-2016. Data from the World Malaria Reports of 2015, 2016 and 2017 (available here.)

However, on a global level, this year’s World Malaria Day comes not without some trepidation. The most recent World Malaria Report, released in late 2017, held some sobering news. For the first time in recent years, progress against malaria appears to have stalled. From 2010 to 2015, there were steady reductions in numbers of malaria cases, mirroring substantial reductions in the number of estimated deaths caused by malaria (see graph). However, in 2016, there were an estimated 5 million more cases worldwide than in 2015, with the number of deaths staying more or less constant, for the first time since 2000.

What could be causing this lack of progress?

First of all, it is worth noting that monitoring and modeling techniques are updated and refined each year; quite often in the World Malaria Reports, numbers from past years are updated to reflect new data or changes in methodology. As such, it may not be until 2018’s World Malaria Report later this year that we get an accurate picture of the scale of the problem.

However, WHO believes there is indeed a real reason behind the stalled progress: reductions in funding. In the countries with the highest burdens of malaria, funding per capita is actually falling. While some of this shortfall may be due to general tightening of budgets for foreign assistance, donor complacency could also be playing a role, with, ironically, the success of malaria control implying that the disease is no longer seen as the urgent threat it once was. With recent media attention on high profile diseases like Ebola—which in its entire history has killed far fewer people than malaria does in an average month—it is not difficult to see how donor attention could have been diverted.

Reductions in funding have been attributed to shortfalls in getting the means to prevent and control malaria—including long-lasting insecticide treated bednets (LLINs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), rapid diagnostics tests, and effective anti-malarial treatments—out to the people who need them the most. However, yet more worrying are the initial signs that some of these tried and tested tools against malaria are no longer working as well as they used to. Partial resistance to the current front-line medications used against malaria, known as artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), has been reported from Asia and South America. Mosquitoes are also increasingly demonstrating resistance to the insecticides used both on long-lasting insecticide treated bednets as well as those used for indoor residual spraying. Despite some promising early findings, the realistic prospect of a commercially available malaria vaccine still seems far away.

So, as World Malaria Day rolls around once more, what next for malaria control? Clearly, we need continue to use the tools we have as effectively as possible: this means continuing to try to get bednets and drugs to all the people who need them, and ensure effective programs of testing and treatment throughout countries where malaria is present, to prevent further spread of drug resistance. Maintaining robust, sustained, and long-term funding will of course also be crucial. Finally, we need to invest in research and development now, before it is too late – a point in time may come when our current tools are no longer effective at all. Given the length of the pipeline for testing new drugs or insecticides, this research needs to be happening now.

Finally, we need to combat complacency. And this is where World Malaria Day really comes into its own – as an opportunity to reflect on the importance of continuing to fight against malaria, and remind ourselves of the importance of working towards the goal of a world where a country like Guinea no longer has to worry about malaria as a public health problem.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.