The proliferation of poor quality medicines has been described as a global pandemic that threatens the lives of millions.1 It stands to reason that poor quality medicines are not going to improve anyone’s health, but how much do we really know about the quality of medicines used across the world? Here we examine five issues relating to medicine quality in an effort to show why we should all be paying more attention to a serious public health issue that is difficult to tackle and not yet fully understood.

1) Definitions

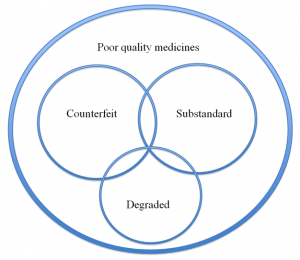

Poor quality medicines are generally divided into three main categories–substandard,degraded and falsified.

Figure 1. A Venn diagram illustrating public health–oriented definitions of poor quality medicines. In the diagram above the relative sizes of the circles and their overlap are not evidence-based as the data available are insufficient to determine this. Source: PLOS Medicine – DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001139 (Creative Commons license).

Substandard medicines result from negligence and errors made during the manufacturing process. Degraded medicines are good quality medicines that have deteriorated, because of inappropriate storage, without refrigeration in hot climates, for instance.

Falsified (or fake) medicines, on the other hand, are the result of deliberate criminal activity. They purport to be real, authorised medicines but usually have packaging that are copies of the genuine product. They may contain active ingredients in the incorrect amount, the wrong active ingredients, or may contain no active ingredients at all.

Substandard and falsified medicines should not be confused with approved generic medicines that are as efficacious as the original innovator product. Generic medicines play a huge role in making medicines accessible as they are generally more affordable; many health programmes around the world rely upon them.

There is no globally recognised consensus on the precise definitions of falsified and substandard medicines. Different organisations and countries use different definitions, and many use the term ‘counterfeit’ to cover infringement of intellectual property (IP). The term ‘falsified’ is increasingly used, devoid of IP connotations, to emphasise the public health consequences. It is not just the terminology that differs; there are differences in opinion regarding the levels of active ingredients that make a drug substandard. India’s medicine regulators suggest that manufacturers should not be sanctioned provided they are using at least 70 per cent of the correct active ingredients, though this level would be regarded as unacceptable in many other countries.2

2) Scale

The available evidence suggests that there is an important global problem. However, the reality is that we do not know its true scale. Many countries have inadequate surveillance systems, and poor quality medicines are often not detected or reported.

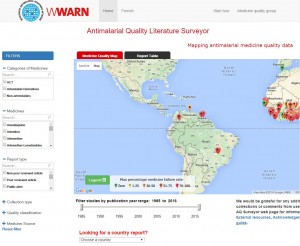

The WWARN Antimalarial Quality Surveyor is an online tool that maps and tabulates published reports about the quality of antimalarial medicines. It was the first open access, independent, global repository and map of its kind, and was designed to help fill some of the information gaps relating to poor quality antimalarials.

WWARN tabulates and maps published reports of antimalarial medicine quality, displaying their geographical distribution across regions and over time.3 No publicly available reports have been found for 60.6% of the 104 malaria-endemic countries and almost one-third of the antimalarials tested from 1946 to 2013 failed chemical and/or packaging analysis.4 However, these results should be viewed with caution because much of the evidence available in the literature is based on surveys that use convenience sampling rather than random sampling to collect the medicines investigated for authenticity; this may lead to under- or over-estimations of the prevalence of poor quality medicines.

Whilst poor quality medicines threaten the huge progress made in combatting diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, the issue is not confined to low income countries. There have been many reports of poor quality medicines and medicinal products, such as cancer therapies, erectile dysfunction products, cholesterol lowering medicines and vitamin supplements, in high and middle income countries. The number of published papers on the subject has increased greatly and more and more countries are reporting breaches of supply chain regulations and falsified medicines.

Falsified medicines are lucrative and there seems to be no shortage of people who are willing to risk the lives of vulnerable patients for profit. It has been estimated that falsified medicines result in $75 billion in illegal annual revenues to criminals.5Poor quality antimalarials were estimated to be associated with the deaths of around 122,350 children under five in 39 countries in sub-Saharan Africa in 2013.6These are very rough estimates as the evidence base is poor.

Whilst efforts are being made to improve surveillance systems, the nature of criminal activity means that those trying to tackle the issue of falsified medicines are dealing with a constantly moving target.

3) Impact

Poor quality medicines have a negative impact on individual patients, healthcare systems, and our ability to deal with a variety of diseases that can be prevented and treated. The consequences of poor medicine quality for patients include: prolonged sickness, treatment failure, side effects, loss of income, and death.

Examples are numerous in the literature. In the 1990s, the consumption of paracetamol syrup wrongly prepared with diethylene glycol led to over 100 deaths in Haiti and India. In 2003, an unusually high incidence of malaria cases was observed in refugee camps in Pakistan because of substandard antimalarials. In 2015, in Central Africa, more than 900 patients suffered from acute dystonic reaction of the face, neck and tongue, because of falsified diazepam that in fact contained the antipsychotic haloperidol.

The impact on healthcare systems includes increased healthcare costs, and loss of public trust which can jeopardise years of investment.7Moreover, poor quality medicines are likely to be a key driver of antimicrobial resistance.2 Antimicrobial resistance develops most rapidly when medicines have enough active ingredients to kill the weaker strains of a pathogen, but not enough to kill the resistant strains. Sub-therapeutic doses selectively kill the susceptible strain, leaving the resistant strain to multiply. Resistance to the most effective malaria treatments threatens to undo the huge gains that have been made in tackling the disease, and is a particular concern when there are so few new antibiotics and antimalarial medicines on the horizon.

4) Clinical trials

Clinical trials are expected to be a trusted method of providing the evidence needed to determine whether medicines are safe, work well and are cost effective. Many healthcare policy decisions are based on clinical drug trial results.

However, clinical trials may involve poor quality medicines. A study of the antimalarial drug sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in pregnant women in Africa was planned using four locally available brands; one of the brands was found to contain less than 90% of the manufacturer’s stated amount of sulfadoxine.8

A cardiac drug shipment worth £1 million was sent from the UK to a pharmaceutical company in the USA in 2007, for use as a comparator in a clinical trial. Suspicions raised by the tablets’ weight led to the discovery that the entire consignment was falsified, containing only 50-80% of the drug stated in the consignment.8

Calls have been made for clinical practice guidelines to include a requirement to determine and state the quality of drugs used in all studies and to include clear guidance on how to monitor and safeguard the quality of medicines used in trials. Otherwise, poor quality medicines used in clinical research may waste time and resources, provide misleading conclusions, cause adverse events in patients, and inappropriately inform public health policy.8

5) Complexity

Poor quality medicines have far-reaching consequences, but our ability to tackle the issue is hampered by its complexity. Criminals are becoming more sophisticated, using the internet as well as offline pharmacies for distribution, creating falsified medicines that are hard to detect, and working across geographical boundaries and in countries with varying legislation and levels of enforcement. Furthermore, the issue affects a broad range of stakeholders from individual patients and pharmacists to politicians and law enforcement agencies.

We need to better understand the scale of the problem and the most affected areas, and raise adequate awareness with all stakeholders. The solution to the problem can only come from collaborative work between governmental authorities, pharmaceutical suppliers, healthcare professionals, and research institutions.

Other articles in this series:

- Five Things You Might Not Know About Medicine Quality

- How Can We Detect Poor Quality Medicines?

- Challenges in Tackling the Issue of Poor Quality Medicines

- Hot Spots: Recent Evidence on the Quality of Currently Recommended Antimalarials

1. Nayyar GM, Breman JG, Herrington JE. ‘The global pandemic of falsified medicines: laboratory and field innovations and policy perspectives.’ Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015 Jun;92(6 Suppl):2-7. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0221. Epub 2015 Apr 20.

- Pisani, E. ‘Antimicrobial resistance: What does medicine quality have to do with it?’ paper for the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. September 22, 2015. Available at http://www.ternyata.org/policy-analysis/medicine-quality/

- WWARN Antimalarial Quality Literature Surveyor, available at http://www.wwarn.org/aqsurveyor/

- Tabernero P, Fernández FM, Green MD, Guerin PJ, Newton PN (2014) Mind the gaps – the epidemiology of poor-quality anti-malarials in the malarious world – analysis of the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network database. Malaria Journal 13, 139.

- BlackstoneEA, Fuhr JP Jr., Pociask S, 2014. ‘The health and economic effects of counterfeit drugs.’ Am Health Drug Benefits 7: 216–224

- Renschler JP, Walters K, Newton P, Laxminarayan P, 2015. ‘Estimating under-five deaths associated with poor quality antimalarials in sub-Saharan Africa.’Am J Trop Med Hyg92 (Suppl 6): 119–126

- Newton PN, Green MD, Fernández FM. Impact of poor-quality medicines in the “developing” world.Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2010;31(3-3):99-101. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.005.

- Newton et al. Quality assurance of drugs used in clinical trials: proposal for adapting guidelines. British Medical Journal. February 25 2015. DOI 2015;350:h602

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.