The global malaria burden is huge. Approximately 3.3 billion people—50% of the world’s population—live in areas of malaria transmission. Of these, approximately 125 million are pregnant. According to estimates by the World Health Organization, there were approximately 198 million cases of malaria in 2013, which led to 584,000 deaths. Malaria in pregnancy is thought to contribute to up to 10,000 maternal deaths and 200,000 infant deaths each year.

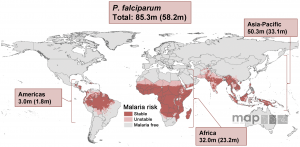

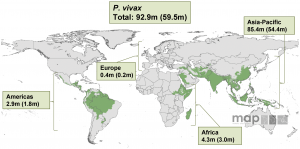

Plasmodium falciparum (the most common type of malaria, and the one that usually causes the most severe illness) infection in pregnancy is the most studied, although there is emerging evidence of the significance of P. vivax infection. In 2007, 85 million pregnancies occurred in areas of P. falciparum transmission, 93 million in areas of P. vivax transmission, and 53 million in areas where both species coexist.

Geographic distribution

Malaria risk map for P. falciparum and corresponding number of pregnancies in each continent in 2007, from Dellicour et al., 2010.

Africa has the greatest morbidity and mortality of P. falciparum infection in pregnancy, where approximately 26% of all pregnancies (range 5-52%) have evidence of infection at the time of delivery. In these regions, malaria transmission is generally stable, year-round, and highly prevalent. Pregnant women are more likely to have no symptoms, and infection causes severe maternal anemia, preterm birth, low birth weight, and maternal death. Over 90% of malaria-related deaths occur in children <5 years of age, and malaria in pregnancy is thought to contribute to at least 11% of the 1.1 million neonatal deaths within 28 days of birth in these areas.

Outside of Africa, where P. falciparum transmission is usually in areas of low, unstable, or seasonal transmission, less is known about the epidemiology of malaria in pregnancy. In these areas, P. falciparum infection is more likely to result in miscarriage, fever, preterm labor, and stillbirth. In Asia and the Americas, P. vivax transmission is more widespread. Although P. vivax causes a milder form of the disease in non-pregnant patients, in pregnancy, it is a significant cause of symptomatic malaria, maternal anemia, and low birth weight. It is estimated to contribute to up to 12% of maternal deaths in these regions.

Malaria risk map for P. vivax and corresponding number of pregnancies in each continent in 2007, from Dellicour et al., 2010.

Consequences of Malaria in Pregnancy – Beyond the Pregnancy

Malaria in pregnancy causes significant consequences for the infant—both immediate and long-term. First, malaria in pregnancy is a prominent cause of low birth weight, which is the most significant single risk factor for neonatal death in developing countries. Low birth weight (defined as less than 2500g) due to malaria infection is from either premature birth (when the baby is born too early) or intrauterine growth restriction (where the baby fails to meet its full growth potential in utero). Malaria in pregnancy causes up to 25% of low birth weight infants in endemic regions. These tiny babies start their lives already at a significant risk of neonatal mortality.

If the baby is able to survive past the immediate newborn period, there are still many obstacles to his survival. Babies born to mothers that had malaria during their pregnancy are at an increased risk of contracting malaria infection during their first year of life, even after controlling for potential confounding environmental factors. These babies have defective immune responses to malaria as infants, perhaps because their in utero exposure made their immune systems more tolerant of malarial antigens. Malaria infection during pregnancy is also an independent risk factor for poor growth during the first year of live, even when controlled for birth weight and other potential confounders.

This photo, showing an antenatal clinic’s register in a rural part of Uganda, shows how common it is for their pregnant patients to present with malaria.

Reducing the burden

The World Health Organization Roll Back Malaria Program has identified preventing malaria in pregnancy as a priority objective in the fight against preventable malaria morbidity and mortality. Intermittent preventative therapy in pregnancy (ITPp), where pregnant women at risk of malaria receive single dose malaria treatment throughout pregnancy, is an effective intervention. It has been shown to reduce maternal anemia by 38%, low birth weight by 43%, and neonatal mortality 27%. The WHO target goal for 2015 is for every pregnant woman at risk of malaria to receive ITPp. However, significant work needs to be done, as only 57% of pregnant women received at least one dose of ITPp, and only 17% received the recommended 3 doses during pregnancy. Clearly additional efforts are needed to save mothers and babies from this preventable disease.

References:

- WHO World Malaria Report 2014

- Dellicour S, Tatem AJ, Guerra CA, Snow RW, ter Kuile FO (2010) “Quantifying the Number of Pregnancies at Risk of Malaria in 2007: A Demographic Study.” PLoS Med 7(1): e1000221. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000221

- Guyatt and Snow (2004) “Impact of Malaria during Pregnancy on Low Birth Weight in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews; 760-769.

- Desai M, ter Kulie FO, Nosten F, et al. (2007) “Epidemiology and Burden of Malaria in Pregnancy.” Lancet Infect Dis; (2)93-104.

About the Author

Stephanie Valderramos is an obstetrician and Maternal-Fetal Medicine Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles. She has been working in the malaria field for over 15 years–first as a Peace Corps Volunteer preventing malaria transmission in Honduras, then as a PhD candidate studying Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance mechanisms, and now as a perinatologist investigating malaria in pregnancy. Her current research focuses on the role of fetal immunity on poor fetal growth in placental malaria. Her work is funded by the National Institutes of Health Reproductive Scientist Development Program.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.