By Charlotte Follari, Norma Quintanilla, and Emily Shambaugh

Malaria is one of the world’s most widespread and deadly infectious diseases, with nearly half of the world’s population at risk of exposure. One of the major barriers to effective malaria control, and the reason why it remains such an entrenched public health problem, is that risk of exposure, and access to control interventions, remain closely tied with social, economic, and environmental determinants. In this blog, we explore the determinants of malaria, with specific reference to the country with the single largest contribution to malaria cases worldwide: Nigeria.

Why focus on determinants?

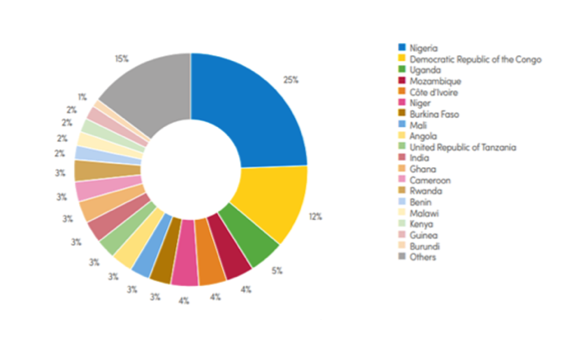

In 2018, malaria cases in Nigeria accounted for 25% of the global burden of disease and 11.16% of the country’s disability adjusted life years (DALYs), despite being preventable through simple yet effective interventions, and treatable with reliable therapies (WHO, 2003). Across the globe, researchers predict that the death toll of malaria will double in the next 20 years if there are no new interventions (Weli & Efe, 2015). However, without understanding the determinants of malaria in endemic countries, interventions may struggle to make a sustainable impact. To this end, it is critical to investigate the social, ecological, and biological determinants of malaria risk, in order to develop culturally-tailored, ecologically-appropriate intervention strategies that will be sustainable in the local context.

Social barriers hinder the impact of interventions

When looking at social determinants of malaria in Nigeria, two factors stand out: education and income. Currently, 40% of Nigerians are living in poverty (World Bank, 2018) and less than 75% have completed primary school (World Bank, 2010). In rural areas throughout the country, high levels of poverty and low levels of education are considered to be malaria risk factors (Adefemi et al., 2015). Poverty is itself a key determinant of health and specifically of malaria, with impoverished populations less likely to live in housing that prevents mosquito entry (i.e. by having screens), to have access to healthcare for diagnosis and treatment for malaria, and to have lower nutritional status, placing individuals, and especially children, at higher risk of severe disease outcomes. Poverty is also correlated with lower educational attainment. Fewer years of formal education can itself be a risk factor; this is because schooling can provide opportunities to learn about malaria transmission; lack of understanding of malaria causes can impede prevention and control efforts, and can also affect people’s willingness to participate in interventions.

Additionally, low levels of education and widespread poverty can affect malaria awareness. According to researchers, awareness about malaria throughout Nigeria is generally low. A studey a few years ago among the Ibo people, for example, observed that less than 50% of people knew that malaria is transmitted through mosquitoes bites (Adefemi et al., 2015). Without malaria awareness, interventions are unlikely to have a sustainable impact. The same study emphasized that written public health information campaigns will have limited reach in rural communities where many people are illiterate. However, campaigns that pair social behavior change messaging with insecticide-treated net (ITN) distribution have led to improved ITN coverage across socioeconomic strata (Zalisk et al., 2019). As a result, the social determinants of malaria should be a key consideration when designing interventions in any country.

Nigeria’s ecology is the ideal setting for vector reproduction

In addition to these social determinants of malaria, there are several ecological factors that influence malaria transmission in Nigeria. Mosquito vectors of malaria are adept at exploiting a variety of environments for reproduction, though they are influenced by factors such as temperature, pH, and salinity (Mutero, 2004). The country’s tropical climate is the ideal environment for vector reproduction, due to high temperatures, precipitation, and humidity, especially in the southeastern regions. For example, Imo State is home to more than three types of forest, including moist lowland tropical forest, freshwater swamp forest and saltwater swamps (Okoji, 2001). Climate variation directly influences the epidemiology of Plasmodium parasites. Tropical, deciduous rainforests in the Imo State region provide various micro- and macro habitats for malaria-transmitting species of mosquito, including Anopheles and Culex (Anosike J C, et al, 2007). In these regions, a two-season rotation dominates between wet season and dry season. Seasonal rainfall that is protected from evaporation by dense canopies provides year-long mosquito habitats. Additionally, increases in temperature and precipitation have appeared to correlate with the projected increased prevalence of malaria in the Imo State region between 1950 and 2014 (Okoji, 2001).

In addition to the natural ecology of Nigeria, increasing human interaction with their environment promotes the transmission of malaria. For example, the rural poor are largely reliant on wood as a primary energy source, as 30% of urban populations in the region (Weli &Efe, 2015). Increased commercial logging in the region multiplies malaria risk, as humans venture deeper in remote forest. Moreover, erosion caused by deforestation results in dislocation of water, creating more mosquito breeding environments (Okoji, 2001). Therefore, intervention strategies must take a two-step approach in understanding how both local ecology and the human role within that ecology affect exposure to potential vectors.

Biological factors increase vulnerability of certain groups

Finally, biological determinants of malaria put certain groups at higher risk, such as pregnant women and children. According to Bassey and Izah, 2017, malaria parasite density in human blood is affected by several biological factors, including blood group, rhesus factor age, gender, educational status, pregnancy status and other medical conditions. . For example, children under the age of five are extremely vulnerable because they have not yet developed immunity to the disease. Additionally, malaria infection poses higher risk to pregnant women compared to the general population (Adefemi et al., 2015). Malaria infection during pregnancy is associated with maternal anemia, low birth weight and fetal growth restriction. However, little is still known on the mechanisms of pathogenesis by which malaria causes fetal growth restriction (Umbers et al., 2011 & Agomo et al., 2009). The susceptibility of women and children to malaris intersects with other factors, such as a climate and access to health care and preventive interventions. According to the WHO, ITNs remain the most effective strategy for protecting pregnant women and their newborns against malaria (WHO, 2003). Other approaches include intermittent preventive treatment and prompt case management of malarial illness. Nigeria adopted intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women in 2005, but there is substantial geographic variation in uptake levels, especially with respect to taking all three recommended doses during the course of pregnancy. Availability of interventions may also be an obstacle, due to supply chain shortages or lack of distribution to remote areas. Improved efforts must be made to understand the factors preventing access, and ensuring these comprehensive and tested packages of interventions reach women and their children.

Sustainability of interventions hinges on comprehensive understanding of social, ecological and biological determinants

Based on these factors, understanding the social, ecological, and biological determinants of malaria is critically important in creating robust interventions, and these must be tailored to the unique conditions in a particular setting. The challenges of controlling malaria are not isolated to treating and preventing the disease alone: poverty and poor education hinders community action against the disease; ecological factors and human behavior increase the changes of exposure to vectors; certain individuals will be more affected by parasitemia than others. In contexts like Nigeria, where over 40% of the population lives in poverty, national malaria control efforts, as promoted by the federal government as well as state analogues and international implementing partners, must continue to take into consideration the various determinants of malaria in order to optimize outcomes, and create lasting impact.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.