By Corey Rathe, Sabrina Barrett, Hannah Hidle, Emma Weimer

Malaria is a serious and life-threatening disease – it is also preventable and treatable. So, why does malaria continue to devastate the lives of hundreds of millions each year? Poverty cycles hold much of this responsibility. Disease and suffering are amplified through overwhelming and cyclical traps. Malaria’s burden and most at-risk populations are highly concentrated in poor, tropical areas. By negatively impacting productivity in school and at work, and with the added financial strain of seeking health care, malaria thus prevents these vulnerable populations from achieving economic security or advancement through education, trapping them in generational poverty.

What is a “poverty cycle”?

Poverty cycles are related to many factors of a community, country, or region. Economist Paul Collier defined the four “development traps” to be: conflict, reliance on natural resources, bad governance, and landlocked with bad neighbors. A country that relates to one or more of these development traps may have large proportions of its population suffering from poverty, and in turn, poor health. Health cannot thrive in poverty; poorer people have lower life expectancy and worse health outcomes than more affluent people. Similarly, good health is imperative to increasing socioeconomic status, taking advantage of educational opportunities, and producing economic contribution to society. As explored further in the next section, in many areas these poverty can be even more explicitly described as “malaria traps,” as the result of malaria reinforcing poverty, while poverty reduces the ability to mitigate malaria. Socioeconomic status plays a large role in protecting against and treating malaria; the poorer the country, the higher the likely burden of disease.

How are malaria and poverty linked?

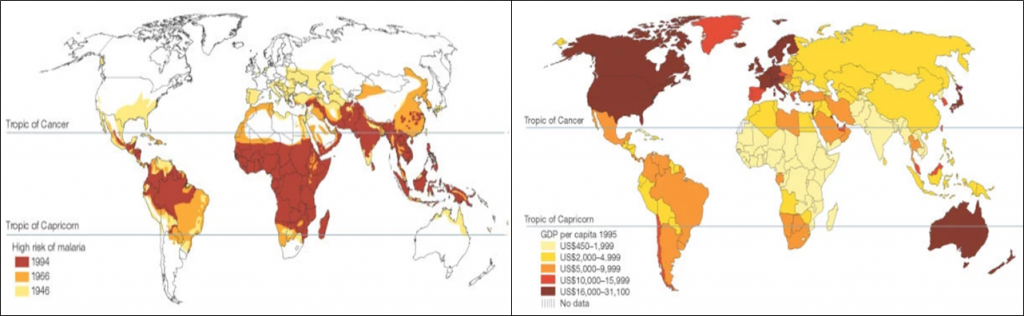

Malaria is able to nestle into poverty cycles incredibly successfully, making the disease a significant challenge for control in poorer communities of the world that populate high risk transmission settings, as seen in Figure 1. In fact, nearly 60% of deaths due to malaria are among the poorest 20% of the global population, and children in the lowest socioeconomic position in a community have double the chance of a malaria infection as children in the highest socioeconomic position in the same community.

Impoverished communities are more likely to have a low level of formal education, which has been associated with a lower likelihood of knowing basic facts about malaria, including how it is contracted. This lack of knowledge surrounding the transmission of malaria may limit the understanding of the potential benefits of prevention and control measures for the disease such as insecticide-treated mosquito nets. In addition, communities may not have consistent access to these measures, or the ability to afford them even when available. Impoverished people are also less likely to be able to afford housing that effectively keeps out malaria-carrying mosquitoes, nor be able to access medical care or afford treatment if and when they do contract malaria.

These compounded impacts mean that poor populations in malaria-endemic areas have both an increased risk of getting malaria and of having a more severe or prolonged case of the disease. When children frequently experience malaria episodes, their attainment in school can be affected, both through absenteeism due to illness as well as lack of concentration or tiredness caused by other effects of the disease, including anemia. Failure to achieve success in school can limit professional options and earning potential; continued exposure to malaria, and episodes of sickness (requiring out of pocket expenditure for travel to seek healthcare and to purchase treatment), in turn reduces the ability to earn and save money. This thereby continues the cycle of poverty and allows malaria to become entrenched in impoverished communities seemingly without end.

What are the solutions?

Despite these challenges, there has been substantial success in reducing both numbers of cases and mortality caused by malaria in the past decade. According to the World Malaria Report, every world region experienced reductions in malaria transmission since 2010, despite ever-increasing population numbers placing more people at risk. However, underdeveloped regions and poor communities continue to be disproportionately burdened by malaria. In countries closing in on elimination, it may be simply a matter of designing and implementing policies that focus on reaching the most vulnerable. For those where control targets remain focused on reducing incidence, lack of access to healthcare remains one of the main challenges. Subsidizing treatment, implementation of vector control, ensuring medicine quality, expanding availability of diagnostics, and providing tailored and audience-appropriate health promotional materials about malaria are all key interventions, which may nevertheless need to be tailored or adapted for uptake among certain at-risk populations. For example, in some countries, extremely impoverished communities do not live in permanent housing structures, making it more challenging to utilize long-lasting insecticide treated bednets, or utilize indoor insecticide sprays to control mosquitoes.

Supporting vertical malaria control efforts with “horizontal” initiatives to expand universal health coverage, as championed by the World Health Organization and espoused by the Sustainable Development Goals, may be one solution. Doing so sustainably will require investments by the governments of malaria-endemic countries in their health systems, and greater efforts to address inequities in health services access, out of pocket costs, and quality of care. These investments will have direct and substantial returns: countries that eliminated malaria were shown to have enjoyed significantly higher economic growth over the five years after elimination than neighboring countries that had not yet eliminated the disease. This once again demonstrates the close linkages between poverty and malaria, and the substantial economic benefits, at the population as well as individual level, that can stem from effective and sustainable malaria control.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.